Southern Syria

Southern Syria (Arabic: سوريا الجنوبية Sūriyā l-Janūbiyya) is a geographical term referring to the southern portion of either Ottoman-period Vilayet of Syria,[1] or modern-day Arab Republic of Syria.

The term was used in the Arabic language primarily from 1919 until the end of the Franco-Syrian war in July 1920, during which the Arab Kingdom of Syria existed.[2][3][4][5]

Zachary Foster in his Princeton University doctoral dissertation has written that in the decades prior to World War I, the term “Southern Syria” was the least frequently used out of ten different ways to describe the region of Palestine in Arabic, noting it was so rare that “it took me nearly a decade to find a handful of references”.[6]

Background

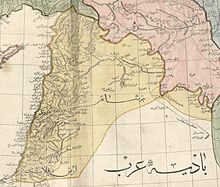

[edit]Throughout the Ottoman period, prior to World War I, the Levant was viewed administratively as part of one province called the Vilayet of Syria, and was divided into districts known as "Sanjaks".

Palestine was by the end of 19th and early 20th century divided into the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem, the Nablus Sanjak, and the Acre Sanjak (under Beirut Vilayet from 1888, and previously under Syria Vilayet), and a short-lived Mutasarrıfate of Karak in Transjordan (split as a new administrative unit from Syria Vilayet in 1894/5).[citation needed] In 1884, the governor of Damascus proposed the establishment of a new Vilayet in southern Syria, composed of the regions of Jerusalem, Balqa' and Ma'an though nothing came out of this.[7]

In the beginning of Faisal’s reign in the Arab Kingdom of Syria, particularly after the San Remo Conference of March 1920, the term "Southern Syria" emerged as a political neologism synonymous with Palestine,[2] and it would take on an increased political significance as a way of rejecting the separation of Palestine from the Kingdom.[8]

Usage during British and French occupation

[edit]In early 20th century, the term "Southern Syria" was a slogan that implied support for a Greater Syria nationalism associated with the kingdom promised to the Hashemite dynasty of the Hejaz by the British during World War I.

After the war, the Hashemite prince Faisal attempted to establish Pan-Levantine state —a united kingdom that would comprise all of what eventually became Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, and Palestine, but he was stymied by conflicting promises made by the British to different parties (see Sykes–Picot Agreement), leading to the French creation of the mandate of Syria and Lebanon in 1920.

One of the resolutions adopted at the first Palestinian Arab Congress in 1919 Jerusalem, was:

"We consider Palestine nothing but part of Arab Syria and it has never been separated from it at any stage. We are tied to it by national, religious, linguistic, moral, economic, and geographic bounds."[9]

Yoav Gelber notes that the Historians of Palestinian Nationalism such as Yehoshua Porath and Muhammad Y. Muslih consider the declaration to be have been ideologically ingenuine, pointing that there was a split among Palestinians regarding the resolutions' implications. The younger generation were eager to pursue political opportunities in a unified Levantine state under Faisal I, and the older generation who wished for Palestine's Independence to maintain their autonomous power in the post-Ottoman world order. Nonetheless, the resolution was mainly supported in the hopes of thwarting support for the Jewish National Homeland that was introduced in the 1917 Balfour Declaration on the occasion of the upcoming San Remo Conference by presenting that Palestine already belongs to another nation than Jews.[10][11] The notables in Faisal's government in Damascus, such as Iraqis and Damascenes, including the Palestinians, had sometimes conflict, and each sought to place their interests above others.[10]

According to the Minutes of the Ninth Session of the League of Nations' Permanent Mandates Commission, held in 1926, "Southern Syria" was suggested by some as the name of Mandatory Palestine in the Arabic language. The reports say the following:

"Colonel Symes explained that the country was described as 'Palestine' by Europeans and as 'Falestin' by the Arabs. The Hebrew name for the country was the designation 'Land of Israel', and the Government, to meet Jewish wishes, had agreed that the word "Palestine" in Hebrew characters should be followed in all official documents by the initials which stood for that designation. As a set-off to this, certain of the Arab politicians suggested that the country should be called 'Southern Syria' in order to emphasize its close relation with another Arab State".[12][13]

In 1932, a Palestinian Arab party named whose name "Hizb Al-Istiqlal" (Independence Party ) was established in Mandatory Palestine by the Sorbonne educated lawyer Awni Abd al-Hadi, whom Daniel Pipes says it the reaffirmed support for the incorporation of Palestine and its people into a Pan-Levantine state.[14]

After when Mandatory Palestine ceased to exist in the aftermath of the Palestine War: the term has been used by Syrian Baathists who sought to expand Syria's borders and justify aggression against Israel, such as Hafiz Al Assad in 1974. The Baathists later went on to create Baathist Palestinian groups such as Al-Saqia in an effort to dominate the PLO and wrest it from Fatah. As of the 1990s Israeli-Syrian peace process, and the Syrian Civil War in the early 2010s: the Baathist party of Syria stopped claiming Israel and the Palestinian territories as "Southern Syria".

References

[edit]- ^ Kazziha, Walid. The Social History of the Southern Syria (Trans-Jordan) in the 19th and Early 20th Century. Beirut Arab University. 1972.

- ^ a b Gerber, Remembering and Imagining Palestine: Identity and Nationalism from the Crusades to the Present, MacMillan, 2008, pp.165–166: “It is interesting that even as late as 1918 Palestine was regarded as an independent entity. Syria was not seen as a mother-country. The idea of amalgamation was to emerge about a month later, following a strenuous campaign by its supporters. But the documents relating to the initiation of the proposed fusion show what was newly constructed and what was the original (and traditional) mode of self-perception. Thus, the document that speaks about the election of candidates to the first Palestinian congress starts by saying inter alia: muqat`at suriyya al-janubiyya al-ma`rufa bi-filastin, that is, the land of Southern Syria, known as Palestine. In other words, what everybody always knew as Palestine is henceforth to be named Southern Syria. Put differently, the writers were fully aware that had they called the country simply Southern Syria, nobody in the Middle East would have known what they were talking about. But no one needed a map or a dictionary to know what the term Palestine meant. This document also offers a simple explanation for the then popularity of the Syrian option: It was simply the case that for a brief moment Syria was an independent, not to say Arab, country. In Palestine everything was different, and the future looked very bleak indeed. The way in which the term Southern Syria was explained by the term Palestine is not confined to a single document. In fact, a more or less similar variant appears in all the documents from this period that mention the term “Southern Syria”: Southern Syria is given as the name of the country, despite the fact that the known term is Palestine. Obviously, Southern Syria was not a traditional name, or even a formal geographical definition. On the contrary, the way in which the term Palestine is always used to explain Southern Syria supports the conclusion that it was quite well known to everybody in the area in 1914 and could not have been invented because of Zionism or for any other reason.”

- ^ Rashid Khalidi, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, Columbia University Press, 2010, pages 165–167

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, pages 35–36.

- ^ Communication from the Arab Revolt in Southern Syria-Palestine (in Arabic) Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Foster, Zachary (November 2017). "Southern Syria". The Invention of Palestine (thesis). Princeton University. pp. 20–21. ISBN 9780355480238. Docket 10634618. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

The Arabs described "the area that became Israel," as Meir put it, in at least ten different ways in the decades prior to World War I, roughly in this order of frequency: Palestine; Syria; Sham; the Holy Land; the Land of Jerusalem; the District of Jerusalem + the District of Balqa + the District of Acre; southern Sham; the southern part of Sham; the Land of Jerusalem + the land of Gaza + the land of Ramla + the land of Nablus + the land of Haifa + the land of Hebron (i.e. cities were used, not regions); "the southern part of Syria, Palestine"; and southern Syria. The Arabic term "southern Syria" so rarely appeared in Arabic sources before 1918 that I've included every reference to the phrase I've ever come across in the footnote at the end of this paragraph (it did appear more often in Western languages). Golda Meir, Mikhaʼel Asaf and my Shabbat hosts were right about Southern Syria, but by focusing only on the facts that supported their arguments and ignoring all the others, they got the story completely wrong. They used facts to obscure the history. If the term rarely appeared in Arabic before World War I, how do propagandists even know it existed? Before World War I, they don't. It took me nearly a decade to find a handful of references, and I can assure you few if any propagandists are familiar with its Arabic usage before 1918. But that changed dramatically in 1918, when the term gained traction for a couple of years until 1920. That's because the Hijazi nobleman Faysal revolted against the Ottoman Empire in 1916 during the First World War (alongside "Lawrence of Arabia"), and established an Arab Kingdom in Damascus in 1918 which he ruled until the French violently overthrew him in 1920. During his period of rule, many Arabs in Palestine thought naively that if they could convince Palestine's British conquerors the land had always been part of Syria—indeed, that it was even called "southern Syria"—then Britain might withdraw its troops from the region and hand Palestine over to Faysal. This led some folks to start calling the place southern Syria. The decision was born out of the preference of some of Palestine's Arabs to live under Arab rule from Damascus rather than under British rule from Jerusalem—the same British who, only a few months earlier, in 1917, had declared in the Balfour Declaration their intention to make a national home for the Jews in Palestine.

- ^ Rogan, Eugene L. (11 April 2002). Frontiers of the State in the Late Ottoman Empire: Transjordan, 1850–1921. Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–55. ISBN 978-0-521-89223-0. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Salim Tamari (2017). The Great War and the Remaking of Palestine. Univ of California Press. p. 3.

Al-Fatat became a leading force in the establishment of the First Syrian government under Prince Faisal. It was during this period that the term Southern Syria became synonymous with Palestine, but the expression gained an added political significance after 1918 – for example, in the creation of Aref and Dajani's newspaper, Surya al-janubiyya, signaling the unity of Jerusalem with Damascus, in response to the British-Zionist schemes of separating Palestine from Syria. In other words, the term Southern Syria, which so far had been a geographic designation, was now explicitly used instead for Palestine as a reaction to the attempts by the British Mandate authorities to excise Palestine from Syria.

- ^ Litvak, Meir (2009). Palestinian Collective Memory and National Identity. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-349-37755-8.

- ^ a b Muslih, Muhmmad (1988). The Origins of Palestinian Nationalism. Columbia University Press. pp. 89–131, 175–191. ISBN 0-231-06508-6.

- ^ Porath, Yehoshua (1974). The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement 1918-1929. Frank Cass: London. pp. 70–123. ISBN 0-7146-2939-1.

- ^ League of Nations, Permanent Mandate Commission, Minutes of the Ninth Session Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Arab Grievances), Held at Geneva from June 8th to 25th, 1926,

- ^ "Mandate for Palestine - League of Nations 9th session- Minutes of the Permanent Mandates Commission". Question of Palestine. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Pipes, D. Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition. Oxford University Press. 1990. p.69.

External links

[edit]- Helsinki.fi−Levant internetcourse: Brief history of Southern Syria Archived 25 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine