Canada–United States border

| Canada–United States border | |

|---|---|

| |

| Characteristics | |

| Entities | |

| Length | 8,891 km (5,525 mi) |

| History | |

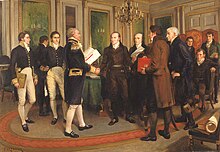

| Established | September 3, 1783 Signing of the Treaty of Paris at the end of the American War of Independence |

| Current shape | April 11, 1908 Treaty of 1908 |

| Treaties | |

| Notes | See list of current disputes |

The international border between Canada and the United States is the longest in the world by total length.[a] The boundary (including boundaries in the Great Lakes, Atlantic, and Pacific coasts) is 8,891 km (5,525 mi) long. The land border has two sections: Canada's border with the contiguous United States to its south, and with the U.S. state of Alaska to its west. The bi-national International Boundary Commission deals with matters relating to marking and maintaining the boundary, and the International Joint Commission deals with issues concerning boundary waters. The agencies responsible for facilitating legal passage through the international boundary are the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

History

[edit]18th century

[edit]

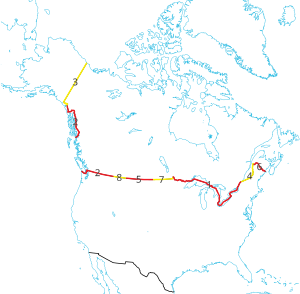

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain and the United States. In the second article of the Treaty, the parties agreed on all boundaries of the United States, including, but not limited to, the boundary to the north along what was then British North America. The agreed-upon boundary included the line from the northwest angle of Nova Scotia to the northwesternmost head of the Connecticut River and proceeded down along the middle of the river to the 45th parallel of north latitude.

The parallel had been established in the 1760s as the boundary between the provinces of Quebec and New York (including what would later become the State of Vermont). It was surveyed and marked by John Collins and Thomas Valentine from 1771 to 1773.[1]

The St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes became the boundary further west, between the United States and what is now Ontario. Northwest of Lake Superior, the boundary followed rivers to the Lake of the Woods. From the northwesternmost point of the Lake of the Woods, the boundary was agreed to go straight west until it met the Mississippi River. That line never meets the river since the river's source is farther south.

Jay Treaty (1794)

[edit]The Jay Treaty of 1794 (effective 1796) created the International Boundary Commission, which was charged with surveying and mapping the boundary. It also provided for the removal of British forces from Detroit, as well as other frontier outposts on the U.S. side. The Jay Treaty was superseded by the Treaty of Ghent (effective 1815) concluding the War of 1812, which included pre-war boundaries.

19th century

[edit]

Signed in December 1814, the Treaty of Ghent ended the War of 1812, returning the boundaries of British North America and the United States to the state they were before the war. In the following decades, the United States and the United Kingdom concluded several treaties that settled the major boundary disputes between the two, enabling the border to be demilitarized. The Rush–Bagot Treaty of 1817 provided a plan for demilitarizing the two combatant sides in the War of 1812 and also laid out preliminary principles for drawing a border between British North America and the United States.

London Convention (1818)

[edit]The Treaty of 1818 saw the expansion of both British North America and the United States, with their boundary extending westward along the 49th parallel, from the Northwest Angle at Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains.[2] While the Laurentian Divide had previously been agreed to as a border, the flatness of the terrain made it difficult to locate this line.[3] The treaty extinguished British claims to the south of the 49th in the Red River Valley, which was part of Rupert's Land. The treaty also extinguished U.S. claims to land north of the 49th in the watershed of the Missouri River, which was part of the Louisiana Purchase. Along the 49th parallel, the border vista is theoretically straight, but in practice follows the 19th-century surveyed border markers and varies by several hundred feet in spots.[4]

Webster–Ashburton Treaty (1842)

[edit]

Disputes over the interpretation of the border treaties and mistakes in surveying required additional negotiations, which resulted in the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842. The treaty resolved the Aroostook War, a dispute over the boundary between Maine, New Brunswick, and the Province of Canada. The treaty redefined the border between New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York on the one hand, and the Province of Canada on the other, resolving the Indian Stream dispute and the Fort Blunder dilemma at the outlet to Lake Champlain.

The part of the 45th parallel that separates Quebec from the U.S. states of Vermont and New York had first been surveyed from 1771 to 1773 after it had been declared the boundary between New York (including what later became Vermont) and Quebec. It was surveyed again after the War of 1812. The U.S. federal government began to construct fortifications just south of the border at Rouses Point, New York, on Lake Champlain. After a significant portion of the construction was completed, measurements revealed that at that point, the actual 45th parallel was three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) south of the surveyed line. The fort, which became known as "Fort Blunder", was in Canada, which created a dilemma for the U.S. that was not resolved until a provision of the treaty left the border on the meandering line as surveyed. The border along the Boundary Waters in present-day Ontario and Minnesota between Lake Superior and the Northwest Angle was also redefined.[5][6]

Oregon Treaty (1846)

[edit]

An 1844 boundary dispute during the Presidency of James K. Polk led to a call for the northern boundary of the U.S. west of the Rockies to be 54°40′N related to the southern boundary of Russia's Alaska Territory. However, Great Britain wanted a border that followed the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean. The dispute was resolved in the Oregon Treaty of 1846, which established the 49th parallel as the boundary through the Rockies.[7][8]

Boundary surveys (mid–19th century)

[edit]The Northwest Boundary Survey (1857–1861) laid out the land boundary. However, the water boundary was not settled for some time. After the Pig War in 1859, arbitration in 1872 established the border between the Gulf Islands and the San Juan Islands.

The International Boundary Survey (or, the "Northern Boundary Survey" in the U.S.) began in 1872.[9] Its mandate was to establish the border as agreed to in the Treaty of 1818. Archibald Campbell led the way for the United States, while Donald Cameron, supported by chief astronomer Samuel Anderson, headed the British team. This survey focused on the border from the Lake of the Woods to the summit of the Rocky Mountains.[10]

20th century

[edit]

In 1903, following a dispute that arose because of the Klondike Gold Rush, a joint United Kingdom–Canada–U.S. tribunal established the boundary of southeast Alaska.[11]

On April 11, 1908, the United Kingdom and the United States agreed, under Article IV of the Treaty of 1908 "concerning the boundary between the United States and the Dominion of Canada from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean", to survey and delimit the boundary between Canada and the U.S. through the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes, by modern surveying techniques, and thus accomplished several changes to the border.[12][13] In 1925, the International Boundary Commission's temporary mission became permanent for maintaining the survey and mapping of the border; maintaining boundary monuments and buoys; and keeping the border clear of brush and vegetation for 6 m (20 ft). This "border vista" extends for 3 m (9.8 ft) on each side of the line.[14]

In 1909, under the Boundary Waters Treaty, the International Joint Commission was established for Canada and the U.S. to investigate and approve projects that affect the waters and waterways along the border.

21st century

[edit]As a result of the 2001 September 11 attacks, the U.S. declared a level 1 alert at its borders, which required intrusive inspections of all crossing vehicles and passengers, resulting in considerable border congestion.[15][16][17] Canada's Chrétien government worked with the U.S. Bush administration to make the border both more secure and less of an impediment for high-value goods and low-risk travellers, and on 12 December 2001 the Smart Border Declaration was signed.[15][18][19][20] The agreement pioneered border innovations that have become common worldwide, such as cargo and passenger preclearance, the Free and Secure Trade (FAST) program, and the NEXUS trusted traveller program.[16] [15] The mutual cooperation established by the Smart Border initiative made it easier to restrict border traffic during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.[16][21]

2020–2021 closure

[edit]

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada and the United States, the governments of Canada and the United States agreed to close the border to "non-essential" travel on March 21, 2020, for an initial period of 30 days.[22] The closure was extended 15 times. In mid-June 2021, the Canadian government announced it would ease some entry requirements for fully vaccinated Canadian citizens, permanent residents, and foreign nationals starting on July 5.[23][24][25][26][27][28] The closure finally expired on July 21. In mid-July, the Canadian government announced that fully vaccinated American citizens and permanent residents could visit Canada starting August 9. The American government reopened its land border to fully vaccinated Canadian citizens effective November 8. The 2020–21 closure was reportedly the first long-term blanket closure of the border since the War of 1812.[29]

Business advocacy groups, noting the substantial economic impact of the closure on both sides of the border, called for more nuanced restrictions in place of the blanket ban on non-essential travel.[30] The Northern Border Caucus, a group in the U.S. Congress composed of members from border communities, made similar suggestions to the governments of both countries.[31] Beyond the closure itself, US President Donald Trump also initially suggested the idea of deploying United States military personnel near the border with Canada in connection with the pandemic. He later abandoned the idea following vocal opposition from Canadian officials.[32][33]

Security

[edit]Law enforcement approach

[edit]The International Boundary is commonly said to be the world's "longest undefended border", though this is true only in the military sense, as civilian law enforcement is present.[34] It is illegal to cross the border outside border controls, as anyone crossing the border must be checked per immigration[35][36] and customs laws.[37][38] The relatively low level of security measures stands in contrast to that of the United States–Mexico border (which is one-third the length of the Canada–U.S. border), which is actively patrolled by U.S. Customs and Border Protection personnel to prevent illegal migration and drug trafficking.

Parts of the International Boundary cross through mountainous terrain or heavily forested areas, but significant portions also cross remote prairie farmland and the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River, in addition to the maritime components of the boundary at the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans. The border also runs through the middle of the Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne and even divides some buildings found in communities in New England and Quebec.

The US Customs and Border Protection identifies the chief issues along the border as domestic and international terrorism; drug smuggling and smuggling of products (such as tobacco) to evade customs duties; and illegal immigration.[39] A June 2019 U.S. Government Accountability Office report identified specific staffing and resource shortfalls faced by the CBP on the Northern border that adversely affect enforcement actions; the U.S. Border Patrol "identified an insufficient number of agents that limited patrol missions along the northern border" while CBP Air and Marine Operations "identified an insufficient number of agents along the northern border, which limited the number and frequency of air and maritime missions."[39]

There are eight U.S. Border Patrol sectors based on the Canada–U.S. border, each covering a designated "area of responsibility"; the sectors are (from west to east) based in Blaine, Washington; Spokane, Washington; Havre, Montana; Grand Forks, North Dakota; Detroit, Michigan; Buffalo, New York; Swanton, Vermont; and Houlton, Maine.[39]

Following the September 11 attacks in the United States, security along the border was dramatically tightened by the two countries in both populated and rural areas. Both nations are also actively involved in detailed and extensive tactical and strategic intelligence sharing.

In December 2010, Canada and the United States were negotiating an agreement titled "Beyond the Border: A Shared Vision for Perimeter Security and Competitiveness" which would give the U.S. more influence over Canada's border security and immigration controls, and more information would be shared by Canada with the U.S.[40][34]

Security measures

[edit]

Residents of both nations who own property adjacent to the border are forbidden to build within the 6-metre-wide (20 ft) boundary vista without permission from the International Boundary Commission. They are required to report such construction to their respective governments.

All persons crossing the border are required to report to the customs agency of the country they have entered. Where necessary, fences or vehicle blockades are used. In remote areas, where staffed border crossings are not available, there are hidden sensors on roads, trails, railways, and wooded areas, which are located near crossing points.[41] There is no border zone;[42] the U.S. Customs and Border Protection routinely sets up checkpoints as far as 100 miles (160 km) into U.S. territory.[43][44][45][46]

In August 2020, the United States constructed 3.8 km (2.4 mi) of short cable fencing along the border between Abbotsford, British Columbia, and Whatcom County, Washington.[47]

Identification

[edit]

Before 2007, American and Canadian citizens were only required to produce a birth certificate and driver's license/government-issued identification card when crossing the Canada–United States border.[48]

However, in late 2006, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced the final rule of the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative (WHTI), which pertained to new identification requirements for travelers entering the United States. This rule, which marked the first phase of the initiative, was implemented on January 23, 2007, specifying six forms of identification acceptable for crossing the U.S. border (depending on mode):[49][50]

- a valid passport—required to enter by air;

- a United States passport card;

- an enhanced driver's license—issued by the U.S. States of Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Vermont, and Washington, as well as the Canadian Provinces of British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec;[51]

- a trusted traveler program card (i.e. NEXUS, FAST, or SENTRI);

- a valid Merchant Mariner Credential—to be used when traveling in conjunction with official maritime business; and

- a valid U.S. military identification card—to be used when traveling on official orders.

The requirement of a passport or an enhanced form of identification to enter the United States by air went into effect in January 2007; and went into effect for those entering the U.S. by land and sea in January 2008.[48] Although the new requirements for land and sea entry went into legal effect in January 2008, its enforcement did not begin until June 2009.[48] Since June 2009, every traveler arriving via a land or sea port-of-entry (including ferries) has been required to present one of the above forms of identification to enter the United States.

Conversely, to cross into Canada, a traveler must also carry identification, as well as a valid visa (if necessary) when crossing the border.[52] Forms of identification include a valid passport, a Canadian Emergency Travel Document, an enhanced driver's license issued by a Canadian province or territory, or an enhanced identification/photo card issued by a Canadian province or territory.[52] Several other documents may be used by Canadians to identify their citizenship at the border, although such documents must be supported with additional photo identification.[52]

American and Canadian citizens who are members of a trusted traveler program such as FAST or NEXUS, may present their FAST or NEXUS card as an alternate form of identification when crossing the international boundary by land or sea, or when arriving by air from only Canada or the United States.[52] Although permanent residents of Canada and the United States are eligible for FAST or NEXUS, they are required to travel with a passport and proof of permanent residency upon arrival at the Canadian border.[52] American permanent residents who are NEXUS members also require Electronic Travel Authorization when crossing the Canadian border.[52]

Security issues

[edit]Smuggling

[edit]

Smuggling of alcoholic beverages ("rum running") was widespread during the 1920s, when Prohibition was in effect nationally in the United States and parts of Canada.

In more recent years, Canadian officials have brought attention to drug, cigarette, and firearm smuggling from the United States, while U.S. officials have made complaints of drug smuggling via Canada. In July 2005, law enforcement personnel arrested three men who had built a 110-metre (360 ft) tunnel under the border between British Columbia and Washington, intended for the use of smuggling marijuana, the first such tunnel known on this border.[53] From 2007 to 2010, 147 people were arrested for smuggling marijuana on the property of a bed-and-breakfast in Blaine, Washington, but agents estimate that they caught only about 5% of smugglers.[54]

Because of its location, Cornwall, Ontario, experiences ongoing smuggling—mostly of tobacco and firearms from the United States. The neighboring Mohawk territory of Akwesasne straddles the Ontario–Quebec–New York borders, where its First Nations sovereignty prevents Ontario Provincial Police, Sûreté du Québec, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada Border Services Agency, Canadian Coast Guard, United States Border Patrol, United States Coast Guard, and New York State Police from exercising jurisdiction over exchanges taking place within the territory.[55][56]

2009 border occupation

[edit]In May 2009, the Mohawk people of Akwesasne occupied the area around the Canada Border Services Agency port of entry building to protest the Canadian government's decision to arm its border agents while operating on Mohawk territory. The north span of the Seaway International Bridge and the CBSA inspection facilities were closed. During this occupation, the Canadian flag was replaced with the flag of the Mohawk people. Although U.S. Customs remained open to southbound traffic, northbound traffic was blocked on the U.S. side by both American and Canadian officials. The Canadian border at this crossing remained closed for six weeks. On July 13, 2009, the CBSA opened a temporary inspection station at the north end of the north span of the bridge in the city of Cornwall, allowing traffic to once again flow in both directions.[57]

The Mohawk people of Akwesasne have staged ongoing protests at this border. In 2014, they objected to a process that made their crossing more tedious, believing it violated their treaty rights of free passage. When traveling from the U.S. to Cornwall Island, they must first cross a second bridge into Canada, for inspection at the new Canadian border station. Discussions between inter-governmental agencies were being pursued on the feasibility of relocating the Canadian border inspection facilities on the U.S. side of the border.[58]

2017 border crossing crisis

[edit]

In August 2017, the border between Quebec and New York saw an influx of up to 500 irregular crossings each day, by individuals seeking asylum in Canada.[59] As a result, Canada increased border security and immigration staffing in the area, reiterating the fact that crossing the border irregularly did not affect one's asylum status.[60][61]

From the beginning of January 2017 up until the end of March 2018, the RCMP intercepted 25,645 people crossing the border into Canada from an unauthorized point of entry. Public Safety Canada estimates another 2,500 came across in April 2018 for a total of just over 28,000.[62]

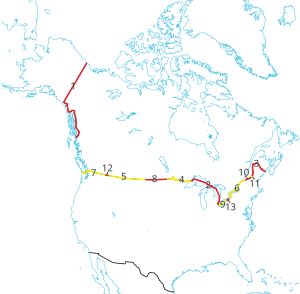

Border lengths and regions

[edit]The length of the terrestrial boundary is 8,891 km (5,525 mi), of which 6,416 km (3,987 mi) is against the contiguous 48 states, and 2,475 km (1,538 mi) against Alaska.[63] Eight out of thirteen provinces and territories of Canada and thirteen out of fifty U.S. states are located along this international boundary.

|

| |||||

| Rank | State | Length of border with Canada | Rank | Province/territory | Length of border with the U.S. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alaska | 2,475 km (1,538 mi) | 1 | Ontario | 2,727 km (1,682 mi) | |

| 2 | Michigan | 1,160 km (721 mi) | 2 | British Columbia | 2,168 km (1,347 mi) | |

| 3 | Maine | 983 km (611 mi) | 3 | Yukon | 1,244 km (786 mi) | |

| 4 | Minnesota | 880 km (547 mi) | 4 | Quebec | 813 km (505 mi) | |

| 5 | Montana | 877 km (545 mi) | 5 | Saskatchewan | 632 km (393 mi) | |

| 6 | New York | 716 km (445 mi) | 6 | New Brunswick | 513 km (318 mi) | |

| 7 | Washington | 687 km (427 mi) | 7 | Manitoba | 497 km (309 mi) | |

| 8 | North Dakota | 499 km (310 mi) | 8 | Alberta | 298 km (185 mi) | |

| 9 | Ohio | 235 km (146 mi) | ||||

| 10 | Vermont | 145 km (90 mi) | ||||

| 11 | New Hampshire | 93 km (58 mi) | ||||

| 12 | Idaho | 72 km (45 mi) | ||||

| 13 | Pennsylvania | 68 km (42 mi) | ||||

Yukon

[edit]The Canadian territory of Yukon shares its entire western border with the U.S. state of Alaska, beginning at the Beaufort Sea at 69°39′N 141°00′W / 69.650°N 141.000°W and proceeding southwards along the 141st meridian west. At 60°18′N, the border proceeds away from the 141st meridian west in a southeastward direction, following the Saint Elias Mountains. South of the 60th parallel north, the border continues into British Columbia.[64]

British Columbia

[edit]

British Columbia has two international borders with the United States: with the state of Alaska along BC's northwest, and with the contiguous United States along the southern edge of the province, including (west to east) Washington, Idaho, and Montana.[65]

BC's Alaskan border, continuing from Yukon's, proceeds through the Saint Elias Mountains, followed by Mount Fairweather at 58°54′N 137°31′W / 58.900°N 137.517°W (near the Fairweather Glacier), where the border heads northwestward towards the Coast Mountains.[65] At 59°48′N 135°28′W / 59.800°N 135.467°W (near Skagway, Alaska), the border begins a general southeastward direction along the Coast Mountains. The border eventually reaches the Portland Canal and follows it outward to the Dixon Entrance, which takes the border down and out into the Pacific Ocean, terminating it upon reaching international waters.

BC's border along the contiguous U.S. begins southwest of Vancouver Island and northwest of the Olympic Peninsula, at the terminus of international waters in the Pacific Ocean and the northwest corner of the American state of Washington.[65] It follows the Strait of Juan de Fuca eastward, turning northeastward to enter Haro Strait. The border follows the strait in a northward direction, but turns sharply eastward through Boundary Pass, separating the Canadian Gulf Islands from the American San Juan Islands. Upon reaching the Strait of Georgia, the border turns due north and then towards the northwest, bisecting the strait until the 49th parallel north. After making a sharp turn eastbound, the border follows this parallel across the Tsawwassen Peninsula, separating Point Roberts, Washington, from Delta, British Columbia, and continues into Alberta.

Prairies

[edit]

The entire Canada–U.S. border in the provinces of both Alberta and Saskatchewan lies along the 49th parallel north.[66][67] Both provinces share borders with the state of Montana, while, farther east, Saskatchewan also shares a border with North Dakota.[67] On the American side, the states of Montana, North Dakota, and Minnesota all lie on the straight part of the border.

Along with the U.S. states of North Dakota and Minnesota (west to east), nearly the entire Canada–U.S. border in Manitoba lies along the 49th parallel north.[68] At the province's eastern end, however, the border briefly enters the Lake of the Woods, turning north at 48°59′N 95°09′W / 48.983°N 95.150°W where it continues into the land along the western end of Minnesota's Northwest Angle, the only part of the United States besides the state of Alaska that is north of the 49th parallel. The border reaches Ontario at 49°23′N 95°09′W / 49.383°N 95.150°W.

Ontario

[edit]

The province of Ontario shares its border (west to east) with the U.S. states of Minnesota, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. The largest provincial international border, most of the border is a water boundary. It begins at the north-westernmost point of Minnesota's Northwest Angle (49°23′N 95°09′W / 49.383°N 95.150°W). From here, it proceeds eastward through the Angle Inlet into the Lake of the Woods, turning southward at 49°19′N 94°48′W / 49.317°N 94.800°W (near Dawson Township, Ontario) where it continues into the Rainy River.[69] The border follows the River to Rainy Lake, then subsequently through various smaller lakes, including Namakan Lake, Lac la Croix, and Sea Gull Lake. The border then crosses the Height of Land Portage over the divide between the Hudson Bay drainage basin, and that of the Great Lakes. The boundary then follows the Pigeon River, which leads it out into Lake Superior. The border continues through Lake Superior and Whitefish Bay, into the St. Mary's River then the North Channel. At 45°59′N 83°26′W / 45.983°N 83.433°W (between Drummond Township, Michigan to the west and Cockburn Island (Ontario) to the east), the border turns southward into the False Detour Channel, from which it reaches Lake Huron. Through the Lake, the border heads southward until reaching the St. Clair River, leading it to Lake St. Clair. The border proceeds through Lake St. Clair, reaching the Detroit River, which leads it to Lake Erie, where it begins turning northeast. From Lake Erie, the border is led into the Niagara River, which takes it into Lake Ontario. From here, the boundary heads northwestward until it reaches 43°27′N 79°12′W / 43.450°N 79.200°W, where it makes a sharp turn towards the northeast. The border then reaches the St. Lawrence River, proceeding through it until finally, at 45°00′N 74°40′W / 45.000°N 74.667°W (between Massena, New York and Cornwall, Ontario), the border splits from the river and continues into Quebec.[69]

Quebec

[edit]The province of Quebec borders (west to east) the U.S. states of New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, beginning where the Ontario-New York border ends in the St. Lawrence River at the 45th parallel north.[70] The Quebec-New York border heads inland towards the east, remaining on or near the parallel, becoming the border of Vermont. At 45°00′N 71°30′W / 45.000°N 71.500°W (the tripoint of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Quebec), the border begins to follow various natural features of the Appalachian Mountains as it turns into the border of Maine. It continues to do so until 46°25′N 70°03′W / 46.417°N 70.050°W (near Saint-Camille-de-Lellis, Quebec on the Canadian side, and unorganized territory on the American side), where it heads north, then northeastward at 46°41′N 69°59′W / 46.683°N 69.983°W (near Lac-Frontière, Quebec). Finally, at 47°27′N 69°13′W / 47.450°N 69.217°W (near Pohénégamook, Quebec), the border heads toward Beau Lake, going through it and continuing into New Brunswick.

New Brunswick

[edit]The entire border of New Brunswick is shared with the U.S. state of Maine, beginning at the southern tip of Beau Lake at 47°18′N 69°03′W / 47.300°N 69.050°W (between Rivière-Bleue, Quebec and Saint-François Parish, New Brunswick), subsequently proceeding to the Saint John River.[71] The border moves through the River until 47°04′N 67°47′W / 47.067°N 67.783°W (between Hamlin, Maine and Grand Falls, New Brunswick), where it splits from the river. It heads southward to 45°56′N 67°47′W / 45.933°N 67.783°W (near Amity, Maine), from whence it follows the Monument Brook further south into the Chiputneticook Lakes, which subsequently leads the border to the St. Croix River. The border proceeds through the St. Croix to Passamaquoddy Bay, which then leads it to Grand Manan Island into the middle of the Bay of Fundy. Here, the border turns towards the south and terminates upon reaching international waters.

Crossings and border straddling

[edit]Airports

[edit]

United States Customs and Border Protection maintains pre-clearance facilities at nine Canadian airports with nonstop air service to the United States: Calgary; Edmonton; Halifax Stanfield; Montreal–Trudeau; Ottawa Macdonald–Cartier; Toronto Island Airport (Billy Bishop Airport), Toronto–Pearson, Vancouver; and Winnipeg James Armstrong Richardson. These procedures expedite travel by allowing flights originating in Canada to land at a U.S. airport without being processed as an international arrival. Canada does not maintain equivalent personnel at U.S. airports due to the limited number of Canada-bound flights from U.S. locations.

Both New York LaGuardia (LGA) and Washington National (DCA) airports lack immigration and customs inspection facilities. However, U.S. pre-clearance facilities in Toronto and Montreal permit nonstop service to New York and Washington.

Cross-border airports

[edit]One curiosity on the Canada–U.S. border is the presence of six airports and eleven seaplane bases whose runways straddle the borderline. Such airports were built before the U.S. entry into World War II as a way to legally transfer U.S.-built aircraft, such as the Lockheed Hudson, to Canada under the provisions of the Lend-Lease Act. In the interest of maintaining neutrality, U.S. military pilots were forbidden to deliver combat aircraft to Canada. As a result, the aircraft were flown to the border, where they landed, and then were towed on their wheels over the border by tractors or horses overnight. The next day, the planes were crewed by RCAF pilots and flown to other locations, typically airbases in Eastern Canada and Newfoundland, from where they were flown to the United Kingdom and deployed in the Battle of Britain.[72]

Piney Pinecreek Border Airport is located in Piney, Manitoba, and Pinecreek, Minnesota. The northwest–southeast-oriented runway straddles the border, and there are two ramps: one in the U.S. and one in Canada. The airport is owned by the Minnesota Department of Transportation.[73]

International Peace Garden Airport is located in Boissevain, Manitoba, and Dunseith, North Dakota, adjacent to the International Peace Garden. The runway is entirely within North Dakota, but a ramp extends across the border to allow aircraft to access Canadian customs. While not jointly owned, it is operated as an international facility for customs clearance as part of the Peace Garden.

Coronach/Scobey Border Station Airport (or East Poplar Airport) is located in Coronach, Saskatchewan, and Scobey, Montana. The airport is jointly owned by the Canadian and U.S. governments, with its east-west runway sited exactly on the borderline.

Coutts/Ross International Airport is located in Alberta and Montana. Like Coronach/Scobey, the east-west runway is sited exactly on the border. The airport is owned entirely by the Montana Department of Transportation (DOT) Aeronautics Division.

Del Bonita/Whetstone International Airport, located in Del Bonita, Alberta, and Del Bonita, Montana, has an east-west runway sited exactly on the border, similar to Coutts/Ross. The airport is officially owned by the state of Montana and run by the state's DOT Aeronautics Division, thus it has been assigned a U.S. identifier only. The facility is set up for both the general public (15 passengers maximum per plane) as well as the American military.[73]

Avey Field State Airport is located in Washington and British Columbia. The privately owned airfield is mostly in the U.S., but several hundred feet of the north-south runway extend into Canada. As such, both Canadian and U.S. customs are available. It is assigned a U.S. identifier but does not have a Canadian one.

Several seaplane bases have water runways that cross the border, though the extent to which they do may be difficult to ascertain. The land-based facilities for the bases are all contained within one country or the other, however, leading to multiple situations where twin seaplane bases may share the same body of water. The following seaplane facilities exist on the border:

- Rouses Point SPB (New York / Quebec)

- Van Buren SPB (Maine / New Brunswick)

- Sault Ste Marie SPB and Sault Ste. Marie Water Aerodrome (Michigan / Ontario)

- Sand Point Lake Water Aerodrome (Minnesota / Ontario)

- International Falls SPB and Fort Frances Water Aerodrome (Minnesota / Ontario)

- Baudette International Airport[b] and Rainy River Water Aerodrome (Minnesota / Ontario)

- Hyder Seaplane Base and Stewart Water Aerodrome (Alaska / British Columbia)[74]

Land border crossings

[edit]

Currently, there are 119 legal land border crossings between the United States and Canada, 26 of which take place at a bridge or tunnel. Only 2 of the 119 crossings are one-way: the Churubusco–Franklin Centre Border Crossing, where travelers may enter only the United States; and the Four Falls Border Crossing, where travelers may enter only Canada.

Six roads have unstaffed road crossings, and do not have border inspection services in one or both directions, where travelers are legally allowed to cross the border. Those who cross are required to report to customs, which are stationed farther within.

Trail crossings

[edit]The Fourth Connecticut Lake Trail (New Hampshire/Quebec) crosses several times while following the border vista before heading back to the United States.

The Pacific Crest Trail crosses into E. C. Manning Provincial Park in the remote North Cascades mountains. Hikers can only legally cross into Canada from the U.S. and not vice-versa, requiring an advance permit.[75]

Rail crossings

[edit]There are 39 railroads that cross the U.S.–Canada border, nine of which are no longer in use. Eleven of these railroads cross the border at a bridge or tunnel.

Only three international rail lines currently carry passengers between the U.S. and Canada. At Vancouver's Pacific Central Station, passengers are required to pass through U.S. partial pre-clearance and pass their baggage through an X-ray machine before being allowed to board the Seattle-bound Amtrak Cascades train, which makes no further stops before crossing the border at Blaine, Washington, where the train stops for another CBP inspection.[76] Pre-clearance facilities are not available for the popular Adirondack (New York City to Montreal) or Maple Leaf (New York City to Toronto) trains, since these lines have stops between Montreal or Toronto and the border. Instead, passengers must clear customs at a stop located at the actual border.

Seaports

[edit]

There are 13 international ferry crossings operating between the U.S. and Canada. Two of them carry passengers only and one carries only rail cars. Four of the ferries operate only on a seasonal basis.

Similar to the pre-clearance facilities at Canadian airports, arrangements exist at major Canadian seaports that handle sealed direct import shipments into the U.S. Along the East Coast, ferry services operate between the province of New Brunswick and the state of Maine, while on the West coast, they operate between British Columbia and the states of Washington and Alaska. There are also several ferry services in the Great Lakes operating between the province of Ontario and the states of Michigan, New York, and Ohio. The ferry between Maine and Nova Scotia ended its operations in 2009, resuming again in 2014.

Seasonal vessel inspection stations are operated at tourist destinations such as Heart Island, New York, and Rockport, Ontario. At landings unmanned by border personnel, telephoning the appropriate border agency may be sufficient to meet legal requirements.[77]

Cross-border buildings

[edit]

A line house is a building located so that an international boundary passes through it. Several such buildings exist along the U.S.–Canada border:

- The Haskell Free Library and Opera House straddles the border in Derby Line, Vermont, and Stanstead, Quebec.

- Private homes divided by the boundary line between Estcourt Station, Maine, and Pohénégamook, Quebec.

- Private homes divided between Beebe Plain, Quebec and Beebe Plain, Vermont;

- A seasonal home divided at the intersection of Matthias Lane in Alburgh, Vermont, and Chemin au Bord de l'Eau in Noyan, Quebec;

- A house divided between Richford, Vermont, and Abercorn, Quebec.[78][79]

- The Halfway House (also known as Taillon's International Hotel) is a tavern, built-in 1820 before the border was surveyed,[80] that straddles the border between Dundee, Quebec, and Fort Covington, New York.[81]

The Maine–New Brunswick border divides the Aroostook Valley Country Club.[82]

Boundary divisions

[edit]Practical exclaves

[edit]To be a true international exclave, all potential paths of travel from the exclave to the home country must cross over only the territory of a different country or countries. Like exclaves, practical exclaves are not contiguous with the land of the home country and have land access only through another country or countries. Unlike exclaves, they are not entirely surrounded by foreign territory. Hence, they are exclaves for practical purposes, without meeting the strict definition.

The term pene-exclave, also known as a "functional" or "practical" exclave,[83]: 31 was defined by G. W. S. Robinson (1959) as "parts of the territory of one country that can be approached conveniently — in particular by wheeled traffic — only through the territory of another country."[84]: 283 Thus, a pene-exclave has land borders with other territories but is not surrounded by the other's land or territorial waters.[85]: 60 Catudal (1974) and Vinokurov (2007)[83]: 31–33 provide examples to further elaborate, including Point Roberts, Washington: "Although physical connections by water with Point Roberts are entirely within the sovereignty of the United States, land access is only possible through Canada."[86]: 113 Practical exclaves can exhibit continuity of state territory across territorial waters but a discontinuity on land, such as in the case of Point Roberts.[83]: 47

Practical exclaves of Canada

[edit]

The Quebec western portion of the Akwesasne reserve is a practical exclave of Canada because of the St. Lawrence River to the north, the St. Regis River to the east, New York State, U.S. to the south. To travel by land to elsewhere in Canada, one must drive through New York State.

Campobello Island is another practical exclave located at the entrance to Passamaquoddy Bay, adjacent to the entrance to Cobscook Bay, and within the Bay of Fundy. The island is part of Charlotte County, New Brunswick, but is physically connected by the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Bridge with Lubec, Maine, the easternmost tip of the continental United States.

Premier, British Columbia is an abandoned mining site accessible only through Hyder, Alaska.

Practical exclaves of the United States

[edit]

Alaska is a non-contiguous U.S. state bounded by the Bering Sea; the Arctic and Pacific oceans; and Canada's British Columbia and Yukon Territory. Additionally, because of the terrain, several municipalities in southeast Alaska (the "Panhandle") are inaccessible by road, except via Canada. Specifically, the town of Hyder, Alaska, is accessible only through Stewart, British Columbia, or by floatplane. Moreover, Haines and Skagway are accessible by road only through Canada, although there are car ferries that connect them to other Alaskan places.

Point Roberts, Washington is bounded by British Columbia, the Strait of Georgia, and Boundary Bay.

In Minnesota, Elm Point, two small pieces of land to its west (Buffalo Bay Point), and the Northwest Angle are bounded by the province of Manitoba and Lake of the Woods.

In Vermont, the Alburgh Tongue, as well as Province Point, which is the small end of a peninsula east of Alburgh, are bounded by Quebec and Lake Champlain.[c]

Split features

[edit]Between Quebec and Vermont, Province Island is a piece of land that primarily lies in Canada, though a small portion of the island is situated in the U.S. state, lying south of the 45th parallel with a border vista marking the international boundary.

Canusa Street in Beebe Plain, VT is the only portion of the Canada–United States border split down the middle of a street.

Between North Dakota and Manitoba, the international border splits a peninsula within a lake on the border of Rolette County, North Dakota, and the Wakopa Wildlife Management Area, MB.[88] Likewise, Lake Metigoshe, lying in the Township of Roland, borders the municipality of Winchester, Manitoba. The border splits a shoreline, putting Canadian cabins on one side and the beach and boat docks for those cabins on the U.S. side, while land access is only through Canada.[89]

Remaining boundary disputes

[edit]

- Machias Seal Island and North Rock (Maine / New Brunswick)

- Dixon Entrance (Alaska / British Columbia)

- Beaufort Sea (Alaska / Yukon)

- Strait of Juan de Fuca (Washington / British Columbia)

See also

[edit]- Canada Border Services Agency

- United States Customs and Border Protection

- Canada–United States relations

- Illegal immigration to Canada

- Illegal immigration to the United States

- Indian barrier state, British plans to set up a new country in the Old Northwest

- John Lewis Tiarks, a British surveyor of the border

- Joseph Smith Harris' account of the Northwest Boundary Survey

- Mexico–United States border

- Mobile Passport, a means of pre-submitting passport information to customs for this border

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The Kazakhstan–Russia border is the world's longest continuous land border.

- ^ Water runway only; land runway does not cross border.

- ^ However, this peninsula and the island to its south are connected by road bridges directly to the United States mainland (as well as by a freight [and former passenger] rail line), such that it is possible to make a through journey in and out of the Alburgh Tongue without entering Canada. This is not true of the other practical exclaves listed here.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Francis M. Carroll (2001). A Good and Wise Measure: The Search for the Canadian–American Boundary, 1783–1842. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division. p. 85.

- ^ "Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America – Signed at London, 20th October 1818". October 20, 1818. Article II. Archived from the original on April 11, 2009.

- ^ Jacobs, Frank (November 28, 2011). "A Not-So-Straight Story". New York Times.

- ^ "Almanac: The 49th Parallel". Sunday Morning. CBS News. October 20, 2013.

- ^ "British-American Diplomacy The Webster-Ashburton Treaty". Yale Law School. 1842. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ Lass, William E. (1980). Minnesota's Boundary with Canada. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. p. 2. ISBN 0-87351-153-0.

- ^ Henry Commager, "England and Oregon Treaty of 1846". Oregon Historical Quarterly 28.1 (1927): 18–38 online.

- ^ Walter N. Sage, "The Oregon Treaty of 1846". Canadian Historical Review 27.4 (1946): 349–367.

- ^ McManus, Sheila (2005). The Line Which Separates: Race, Gender, and the Making of the Alberta-Montana Borderlands. Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-88864-434-5.

called it the Northern Boundary Survey.

- ^ Campbell, Archibald; Twining, W.J. (1878). "Reports upon the survey of the boundary between the territory of the United States and the possessions of Great Britain from the Lake of the woods to the summit of the Rocky mountains". Authorised by an act of Congress approved March 19, 1872. Government Printing Office. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Keenlyside, Hugh LL.; Brown, Gerald S. (1952). Canada and the United States: Some Aspects of Their Historical Relations. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 178–189. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ International Boundary Commission (1937). "Treaty of 1908". Joint report upon the survey and demarcation of the boundary between the United States and Canada from the gulf of Georgia to the northwesternmost point of Lake of the woods. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 6. hdl:2027/mdp.39015027937153.

- ^ International Waterways Commission (1915). "Report of the International Waterways Commission upon the International Boundary between the Dominion of Canada and the United States through the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes as Ascertained and Re-established pursuant to Article IV of the Treaty between Great Britain and the United States signed 11th April 1908".

- ^ Organization Chart, International Boundary Commission. Retrieved July 27, 2007 Archived 2007-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Trautman, Laurie; Alden, Edward (December 13, 2024). "The lessons we learned about cross-border co-operation after Sept. 11 have been forgotten". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ a b c McCarten, James (September 4, 2021). "Canada, U.S. got smart about border 20 years ago, but not smart enough, say critics". Calgary CityNews.

- ^ Brister, Bernard James (2012). "The Same Yet Different: Continuity and Change in the Canada-United States Post-9/11 Security Relationship" (PDF). Canadian Defence Academy Press.

- ^ McLellan, Anne; Manley, John (February 24, 2022). "Canada needs new laws to prevent future blockades of critical infrastructure". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Gray, Jeff (December 12, 2001). "Ridge, Manley sign 'smart border' declaration".

- ^ "Summary of Smart Border Action Plan Status". The White House: President George W. Bush. September 9, 2002.

- ^ Panetta, Alexander (March 20, 2020). "How the shutdown after 9/11 paved the way for the new Canada-U.S. border response to COVID-19". CBC News.

- ^ Office of the Prime Minister (March 20, 2020). "U.S.-Canada joint initiative: Temporary restriction of travelers crossing the U.S.-Canada border for non-essential purposes". Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "Canada-U.S. Land border closure extended to Feb. 21". January 12, 2021.

- ^ "Canada-U.S. border closure extended to Jan. 21 as coronavirus cases soar, CBSA says - National | Globalnews.ca". Global News.

- ^ Aiello, Rachel (July 14, 2020). "Canada, U.S. agree to keep borders closed another 30 days: sources". CTV News.

- ^ Aiello, Rachel (August 14, 2020). "Canada-U.S. border closure extended again amid tension over restrictions". CTV News. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Elaine Glusac (June 29, 2021). "Why Can't Americans Go to Canada?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021.

In mid-June, to the frustration of many on both sides of the border, Canada announced it was extending restrictions on nonessential travel until at least July 21. The ban includes travel via land, air, and sea. The United States closed its border with Mexico contemporaneously with the Canada–U.S. closure.

- ^ Oliver, David (March 19, 2020). "Trump announces U.S.-Mexico border closure to stem spread of coronavirus". USA Today. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Hess, Daniel Baldwin; Bitterman, Alex (May 29, 2020). "Shuttered Canada-US border highlights different approaches to the pandemic – and differences between the 2 countries". The Conversation. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ McCarten, James (June 12, 2020). "Frustration grows with no apparent end in sight for Canada-U.S. border ban". The Canadian Press. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Chapman, Cara (June 15, 2020). "Stefanik, Higgins call for guidance on reopening border". Press-Republican. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Tunney, Catharine; Ling, Philip; Simpson, Katie (March 21, 2020). "U.S. has dropped the idea of placing troops near Canadian border: official". CBC News. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Campion-Smith, Bruce (March 26, 2020). "U.S. backs down after Canada slams proposal for American troops along the border". Toronto Star. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Leuprecht, Christian; Hataley, Todd; Sundberg, Kelly; Cozine, Keith; Brunet-Jailly, Emmanuel (October 2, 2021). "The United States–Canada security community: a case study in mature border management". Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 59 (4): 376–398. doi:10.1080/14662043.2021.1994724. ISSN 1466-2043.

- ^ Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, S.C. 2001, c. 27, s. 18 (Immigration and Refugee Protection Act at Justice Laws)

- ^ 8 U.S.C. § 1324; 8 U.S.C. § 1325; and 8 U.S.C. § 1326.

- ^ Customs Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 1, s. 11

- ^ 19 U.S.C. § 1459.

- ^ a b c CBP Identified Resource Challenges but Needs Performance Measures to Assess Security Between Ports of Entry (PDF) (Report). U.S. Government Accountability Office. June 2019.

- ^ Mark Kennedy, Postmedia News Political Time Bombs Litter Harper's Path Archived 2010-12-16 at the Wayback Machine, December 13, 2010

- ^ Mallonee, Laura (January 4, 2016). "The Invisible Security of Canada's Seemingly Chill Border". Wired. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Common border zone proposed". Canadian Society of Customs Brokers. June 17, 2004. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Singel, Ryan (October 22, 2008). "ACLU Assails 100-Mile Border Zone as 'Constitution-Free' – Update". Wired. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Woodard, Colin (January 9, 2011). "Far From Canada, Aggressive U.S. Border Patrols Snag Foreign Students". Chronicle.com. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Customs and Border Protection". AP News. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ Legrand, Tim; Leuprecht, Christian (2021). "Securing cross-border collaboration: transgovernmental enforcement networks, organized crime and illicit international political economy". Policy and Society. 40 (4): 565–586. doi:10.1080/14494035.2021.1975216.

- ^ Johnston, Patrick (August 20, 2020). "'Fence' south of Aldergrove about road safety and border security, U.S. officials say". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Timeline: Travel documents at the Canada-U.S. border". CBC News. May 12, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative: The Basics". Homeland Security. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ^ "Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative". Bureau of Consular Affairs. U.S. Department of State. January 13, 2008. Archived from the original on January 25, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- ^ "WHTI: Enhanced Drivers License". U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. June 1, 2009. Archived from the original on February 15, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Travel documents and identification requirements". cbsa.-asfc.gc.ca. Government of Canada. March 19, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Frieden, Terry (July 22, 2006). "Drug tunnel found under Canada border: Five arrests made after agents monitored construction". CNN.

- ^ MacDonald, Jake (July–August 2010). "The Canada-U.S. Border". Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on July 10, 2010.

- ^ Royal Canadian Mounted Police, "Fifteen People Arrested for Possession of Contraband Tobacco during High-Intensity Enforcement Project", press release, February 25, 2009 Archived 2011-06-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cockburn, Neco (November 21, 2008). "Smuggling's price". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Cornwall border reopened after Mohawk dispute". CTV News. September 19, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ Sommerstein, David; Canton, in; NY. "New Cornwall bridge opens, but it still feels closed to Mohawks". NCPR. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ "Number Of Asylum Seekers At Quebec Border Nearly Quadrupled In July: Officials". HuffPost. August 17, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Woods, Allan (August 23, 2017). "Canada is not a safe haven for asylum seekers, Trudeau warns". Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Trudeau says steps to tackle spike in asylum-seekers yielding 'positive results'". CBC News. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Fewer than 1% of more than 28,000 irregular asylum seekers have been removed from Canada so far | CBC News".

- ^ "Boundary Facts". International Boundary Commission. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Yukon Territory" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c "British Columbia" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Alberta" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "Saskatchewan" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Manitoba" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "Ontario" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Québec" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "New Brunswick" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Places to Fly – Dunseith / International Peace Garden Archived 2012-06-13 at the Wayback Machine. Archive.copanational.org (June 8, 2007). Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Simpson, Victoria. 2020. "4 Airports Shared By The U.S. And Canada." WorldAtlas. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "13 strange facts about the town of Hyder Alaska". September 11, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ "Canada PCT Entry Permit".

- ^ Fesler, Stephen (November 22, 2019). "Amtrak Cascades Could Get Customs Preclearance in Canada Shaving At Least 10 Minutes Off Trip". The Urbanist. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Best Cruising Destinations: The 1000 Islands". Northern Ontario Travel. September 30, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "1000 Drew Rd – Richford Vermont" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ Farfan, Matthew (2009). The Vermont-Quebec Border: Life on the Line. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-6514-8

- ^ Taillon's International Hotel, Taillon's International Hotel – straddling the US–Canada border! Archived 2010-01-17 at archive.today

- ^ "Wikimapia". Wikimapia. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ Aroostook Valley Country Club, Club History

- ^ a b c Vinokurov, Evgeny (2007). The Theory of Enclaves. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- ^ Robinson, G. W. S. (September 1959). "Exclaves". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 49 (3, [Part 1]): 283–295. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1959.tb01614.x. JSTOR 2561461.

- ^ Melamid, Alexander (1968). "Enclaves and Exclaves". In Sills, David (ed.). International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Vol. 5. The Macmillan Company & Free Press.

Contiguous territories of states which for all regular commercial and administrative purposes can be reached only through the territory of other states are called pene-enclaves (pene-exclaves). These have virtually the same characteristics as complete enclaves (exclaves).

- ^ Catudal, Honoré M. (1974). "Exclaves". Cahiers de géographie du Québec. 18 (43): 107–136. doi:10.7202/021178ar.

- ^ "USGS The National Map: Orthoimagery. Data refreshed October 2017". United States Geological Survey (U.S. Department of the Interior). Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ^ Hutchinson Township. North Dakota: Geo. A. Ogle & Co. 1910. p. 69. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) Note: This lake is located in the former Hutchinson Township in Rolette County on the property shown in this 1910 atlas as owned by A. O. Osthus. The lake otherwise appears to be unnamed. - ^ Laychuk, Riley (July 13, 2016). "Manitoba boaters stunned by new cross-border rule". CBC News. Retrieved June 3, 2017.

In fact, some of the boat docks for Canadian cabins sit on the U.S. side of the border.

Further reading

[edit]- Ackleson, Jason. 2009. "From 'thin' to 'thick' (and back again?): the politics and policies of the contemporary US–Canada border." American Review of Canadian Studies 9.4 (2009): 336-351.

- Anderson, Christopher G. 2012. Canadian Liberalism and the Politics of Border Control, 1867–1967. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. Studies pivotal episodes in Canadian immigration policy that shed light on more restrictive approaches today.

- Andreas, Peter. 2005. "The Mexicanization of the US-Canada border: Asymmetric interdependence in a changing security context." International Journal 60.2 (2005): 449-462.

- Côté-Boucher, Karine, Luna Vives, and Louis-Philippe Jannard. 2023. "Chronicle of a 'Crisis' Foretold: Asylum seekers and the case of Roxham Road on the Canada-US border." Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 41.2 (2023): 408-426. online

- Hunt, Courtney. 2008. Frozen River. edited by Kate Williams. US: Sony Pictures Classics. A feature film about smuggling across the border

- Leuprecht, Christian; Hataley, Todd S., eds. Security. Cooperation. Governance.: The Canada-United States Open Border Paradox (University of Michigan Press, 2023) online review of this book

- Lybecker, Donna L., et al. 2018. "The social construction of a border: The US–Canada border." Journal of Borderlands Studies 33.4 (2018): 529-547.

- McCallum, John. 1995. "National borders matter Canada-US regional trade patterns." American Economic Review 85.3 (1995): 615-623.

- Moens, Alexander, and Nachum Gabler. 2012. "Measuring the costs of the Canada-US border." (Fraser Institute, Studies in Canada-US Relations (2012). online

- Nicol, Heather N. 2012. "The wall, the fence, and the gate: Reflexive metaphors along the Canada–US border." Journal of Borderlands Studies 27.2 (2012): 139-165.

- Nicol, Heather. 2005. "Resiliency or Change? The Contemporary Canada—US Border." Geopolitics 10.4 (2005): 767-790.

- Paulus, Jeremy, and Ali Asgary. 2010. "Enhancing Border Security: Local Values and Preferences at the Blue Water Bridge (Point Edward, Canada)." Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 7(1): article 77.

- Salter, Mark B., and Geneviève Piché. 2011. "The securitization of the US–Canada border in American political discourse." Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique 44.4 (2011): 929-951. online

- Von Hlatky, Stéfanie, and Jessica N. Trisko. 2012. "Sharing the Burden of the Border: Layered Security Co-operation and the Canada–US Frontier." Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique 45.1 (2012): 63-88. online

External links

[edit]- University of Kent. 2015. Culture and the Canada–US Border, funded by Leverhulme Trust. An international research network dedicated to studying cultural representation, production, and exchange on and around the Canada–US border.